Please read in conjunction with the photographs of the Gloucester & Sharpness Ship Canal and Bristol's Floating Harbour in the photojournalism section of this website.

Introduction

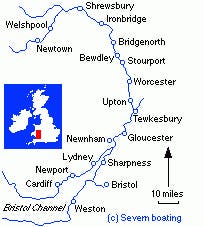

Having cycled along the old canal tow-paths, of many stretches of canal in southern England, I was fascinated by their engineering and beauty and how they became almost redundant in a relatively short space of time. Reading into the history of the these canals, I realised that they were part of a frantic multi-faceted strategic trade trade war between wealthy merchants, regions, cities, industries and their local and international value chains and spheres of operation. And this brought me to discover that one of my local canals was in-fact a ship canal - not just a canal wide enough for two 'narrow' or 'long' boats to pass. Even more impressive, I discovered that the Gloucester & Sharpness Ship Canal was the broadest and deepest in the world when it opened in 1827!

And not only that, I was staggered to discover that the large impressive docks at Gloucester, lined with their imposing yet beautiful brick warehouses, were, like the canal, also dug from the ground in an attempt, by industrialists from Britain's manufacturing capital, Birmingham, and merchants and other influential residents from Gloucester, to tempt trade away from the long established port in Bristol to the South, which in the late 18th century, was the most important port on the western sea board of the United Kingdom (UK) and only second in the UK to London both as a port and a city.

I came to realise the Gloucester & Sharpness Ship Canal, was not just a canal, but a business incubator and a major new trade route connecting the world's biggest manufacturing hub to the Atlantic Ocean, and with it, to the world. The development of the Ship Canal did not happen, as I discovered, alone in splendid isolation, it was part of a much bigger, highly dynamic expansion of the British economy that was the driving force behind the industrial revolution.

The 19th century in particular was a massive period of international trade for Britain, both globally and at home, and much of the profits were ploughed back into investments in infrastructure, not least the most extensive network of navigable inland canals in the world (over 4,000 miles in total!). Development of the UK canal system reached its zenith during the late 18th and early 19th centuries during the so-called 'canal-mania' period. Many of these canals had relatively short commercial lives once 'railway mania' replaced the canal investment boom in the mid 19th century.

The 19th Century saw the rise not only of Gloucester, but much more significantly, the rise of Birmingham and Manchester, as the manufacturing powerhouses of the world, and of Liverpool, which by the end of 18th Century, was not only the most important port in the country, but of the world. It also saw the passing of Britain's canal network, of horse drawn canal barges, and of commercial sailing ships, as well as the rise of the UK's railway network, which like the canal network, was the most extensive in the world at the time.

This little study centred around the rise and fall of the magnificent Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal, has turned out to be a crude attempt to piece together the fascinating fate of England's west coast port cities of Bristol, Gloucester and Liverpool, from the late 18th century onwards, and the engineering marvels that they all left behind.

Bristol Dominates the Atlantic Sea Trade in the Time Before Canals

Bristol was already England’s second largest city by the 1760s. Situated close to Severn Estuary and the inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, known as the Bristol Channel, Bristol was a long established and important international port from which a significant proportion of the goods, in and out of Birmingham, were shipped around the world from. Goods, especially raw materials, arrived in Bristol and needed to be transhipped from the large ships , coming in from the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean via the Bristol Channel, onto smaller vessels for further navigation up the River Severn, past Gloucester, and on to Worcester where the goods were transhipped again for transport by road to Birmingham.

The Hustle by Gloucester to out Manoeuvre Bristol and Capitalise on the Rise of Birmingham and the Midlands as the Workshop of the World

For the industrialists of Birmingham improving the transport infrastructure along their trade routes in England was a necessity if they were to expand their manufacturing businesses. For the merchants of Gloucester, there was a major strategic opportunity to benefit directly from the rapid development of Birmingham as the manufacturing capital of the world. As it turned out the merchants of Gloucester had been tussling with Bristol since the fifteenth century, at least, when the the small river port of Gloucester was under the control of the Port of Bristol. After a hard fought series of court cases with the Bristolian merchants, Gloucester port gained its' independence from Bristol.

I don't expect however, that in the 15th Century, the business interests in Gloucester foresaw the massive transformation of Birmingham to the north, from a small market town with a population of about 1,500 (about the same as the much older City of Gloucester), into a bustling manufacturing town of 74,000 people at the beginning of the 19th Century, that dwarfed Gloucester with a population of just 5,000 by time the idea for the Ship Canal was proposed. Even less likely is that Gloucester would be an important partner in the rise of Birmingham and the West Midlands region of England as the manufacturing centre of the world during the 19th century in particular.

Bristol Losing its Grip on the Burgeoning Sea Trade of the UK's Western Seaboard

This trade war between Gloucester and Bristol reminded me of another trade battle involving Bristol. In 1500, Liverpool was just a fishing village of approximately 600 people situated on the eastern bank of the estuary of the River Mersey, just 3 miles inland from Liverpool Bay where the Mersey enters the Irish Sea, which allowed ships easy access to the the Atlantic Ocean. Despite this highly strategic location close to the Irish Sea, no-one could have expected its rise to global maritime dominance by the end of 18th Century. A major part of its success was its proximity to the manufacturing powerhouse of the north, Manchester, which had begun to expand at an astonishing rate around the end of the 18th century due to its' boom in textile manufacture. As a consequence Manchester become the world's first industrialised city and Liverpool's growth paralleled it.

Competition with Liverpool began around 1760 with the expansion of the docks in Liverpool, and were exacerbated further by disruptions in maritime commerce due to war with France and the abolition of the slave trade (1807), both of which, contributed to Bristol's failure to keep pace with the newer manufacturing centres of Northern England and the West Midlands. The Port of Bristol had major limitations. It was situated 7 miles (11 km) inland on the River Avon and had tides that fluctuated about 30 feet (9 metres) between high and low water. This meant that the river was navigable at high-tide but was reduced to a muddy channel at low tide causing ships to often run aground.

Bristol Fights Back with the Completion of Three World Class Infrastructure Achievements

In 1804 after Parliamentary approval, the construction of a floating harbour to significantly increase Bristol's harbour capacity, and maintain a constant high tide within it, began. The floating harbour was completed in 1809, and while it helped keep the Port of Bristol in business, it was very costly, and resulted in even higher harbour fees, which further diminished Bristol's competitiveness.

The trade war with Liverpool also centred on the desire of Bristol's merchants to cement its' ties with London, and to maintain its importance as the second port of the country after London, and the chief one for American trade. The development of the Great Western Railway (GWR) between Bristol and London originated from this desire, and would not only replace the Kennet and Avon Canal, which fully opened in 1810, as the main route for the transport of goods between Bristol and London, but also compete with the Liverpool to London rail line already under construction in the 1830s. With the co-operation of London interests, they obtained parliamentary permission to build a line of their own; a railway too be built to unprecedented standards of excellence to out-perform the lines being constructed from London to the North West of England. The railway line between London and Bristol fully opened in 1841.

In a further attempt to out compete Liverpool, the Victorian engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, who also constructed the railway, designed and built the pioneering Bristol-built ocean-going steamship the SS Great Western to link Bristol with New York City (NYC). It was the fastest ship of its day and for a while made Bristol the most convenient and fastest passage from which to reach NYC from London. The rise of Liverpool however was unstoppable, and it is said, that Liverpool was already handling 40% of the world's trade through its' docks by the beginning of the 19th century!

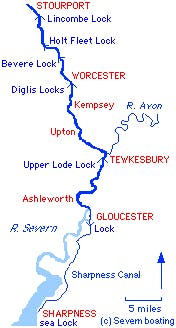

Whether the merchants of Bristol realised they were also in a trade war with Gloucester or not, it is obvious that the Birmingham-Gloucester consortium sensed Bristol's weakness, when in 1793, they successfully obtained an Act of Parliament to construct a ship canal between Gloucester and Berkeley to bypass a treacherous stretch of the River Severn just south of Gloucester. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the River Severn was the second busiest river in Europe, and the longest naturally navigable river in England. While navigation all the way up the Severn to Welshpool, which is way beyond Gloucester, was possible, only small, non-ocean going vessels and barges could navigate through Gloucester and further upstream. Under their proposal sea-going ships would be able to reach Gloucester directly, with the hope that in time, Gloucester would rival Bristol in importance, and raw materials in particular could more easily be imported to Birmingham, and the booming Midlands region of central England as a whole. Work began in 1794 on digging out what was then known as 'The Gloucester and Berkeley Canal', but by the end of the decade, only five miles of the canal had been completed, due to financial pressures and disputes with landowners etc.

Gloucester Cements its Position at the Centre of a Majorly Upgraded Trade Route

Given this was canal mania time, the construction of the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal was not the only canal gig in town! A complimentary canal was also being built that would create a (shorter) link (what was the original link, maybe another canal given the opposition of the other canal companies?) between Birmingham and the River Severn at Worcester, which would enhance the Birmingham to Gloucester trade route. Despite much opposition form other canal companies, an Act of Parliament was obtained in 1791, for the construction of a new, 14 feet double barge width canal, which began construction at the Birmingham end in 1792. The Worcester and Birmingham Canal opened in 1815, some 12 years before the completion of the Gloucester to Sharpness Ship Canal.

The Port of Gloucester Rises from Nowhere

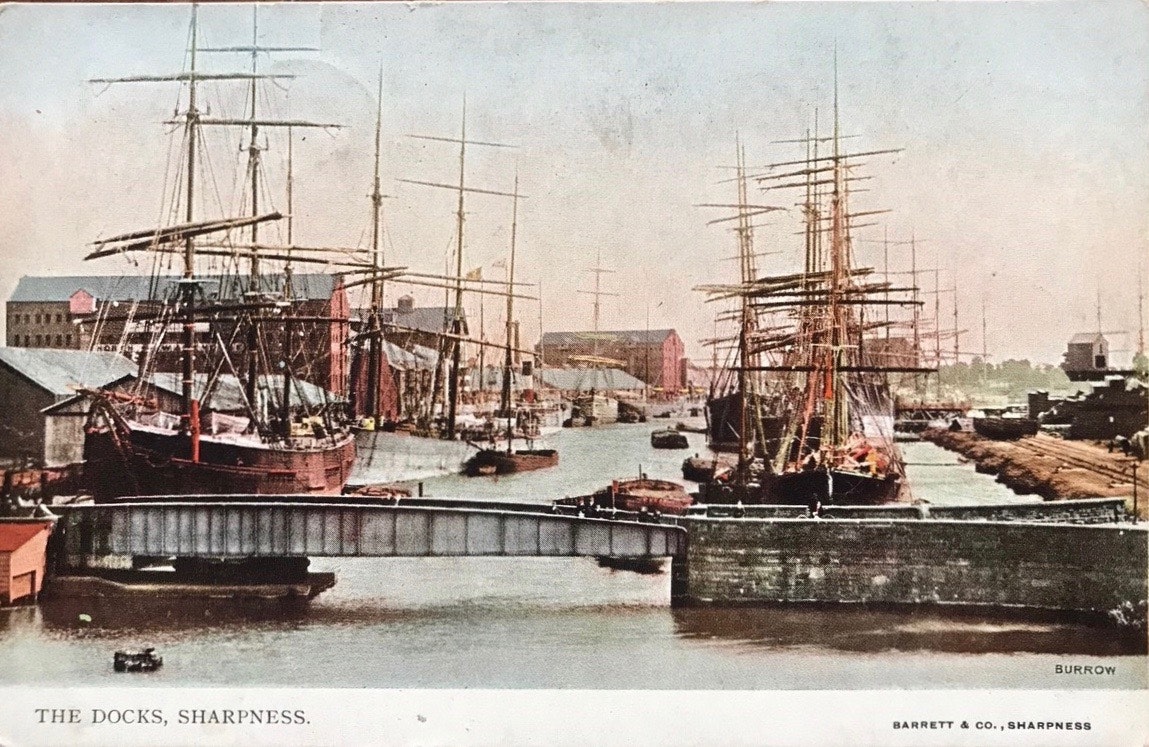

The Gloucester to Sharpness Ship Canal, despite having commenced construction in 1794, made very slow progress until 1816, when it was agreed that the route of the canal should be more direct, and its terminus be at Sharpness, a couple of miles short of the original destination of Berkeley. Work started on the Entrance Basin on the Severn Estuary at Sharpness in 1818 and the canal finally opened in 1827. At 86.5 feet wide, and 18 feet deep, and taking craft of 600 tons (with maximum dimensions of 190 feet long and 29 feet wide), it was apparently the biggest canal in the world at the time.

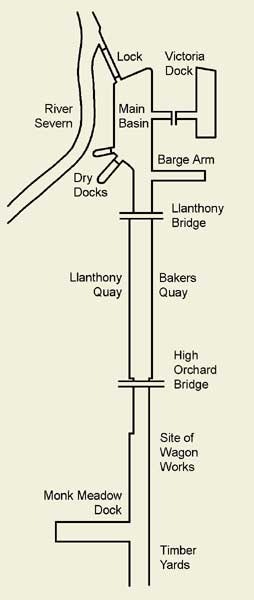

By 1827, it was possible for the biggest ships in the world to sail up the Bristol Channel, into the Seven Estuary, pass Bristol, and enter the Ship Canal at Sharpness and dock in the Main Basin at Gloucester. Goods could then be transhipped onto smaller canal / river boats that would enter the Severn via the lock in the Main Basin of the docks, and travel upstream to Worcester, where they could enter the new Worcester and Birmingham Canal before proceeding to unload their goods in Birmingham, close to the factories that ordered them.

The Main Basin also included a narrow dock, referred to as a 'Barge Arm', to accommodate small vessels bringing goods for local distribution that didn't need to moor close to the larger vessels. With the Ship Canal fully operational, local merchants could import through Gloucester, instead of Bristol, which not only cut out the need for transshipment at Bristol, but also avoided the high port fees charged in Bristol. The first two ships to pass through the canal were Meredith, with a cargo of brandy from France, and Annie, which came from Bristol to pick up salt for the Newfoundland fisheries. There were tales at the time, from astonished local people, of tall-masted sailing ships floating through the fields of Gloucestershire.

Foreign Imports Boom and Gloucester Capitalises

The geographical position of Gloucester so far inland was a huge advantage, and traffic exceeded all expectations. As well as the lighters, sloops, trows and barges that were already in use in the existing river and coastal trade, especially between Bristol and the upstream towns in the Midlands, there were increasing numbers of two-masted brigs, two or three-masted schooners and some three-masted barques. Early imports into Gloucester included corn from Ireland and the continental Europe , timber from the Baltic and North America, and wines and spirits from Portugal and France. The main export out of Gloucester was salt which was brought down the Severn from Worcestershire and used by the Newfoundland fishing fleet that operated by interests in Bristol.

The early success of the Ship Canal resulted in additional warehouses being built around the Main Basin, an earlier dry dock being enlarged, and an engine house being built to pump water from the Severn to maintain the canals water level. In order to extend frontage for ships to dock, Bakers Quay was constructed along the canal which mainly serviced timber yards. Interestingly several of the yards were locked-up under customs supervision so that foreign timber could be stored without paying import duty. Some of the ships bringing timber from North America were locally owned, and they often carried emigrants on the outward journey. Success continued, and in 1849, the Victoria Dock was opened to the east of the Main Basin, with a narrow cut linking the two to relieve congestion and delays. Foreign imports in particular were booming due to the popular national movement at the time to reduce import duties, especially after the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846. In addition to the new dock, corn warehouses were built and more timber yards were established.

The Railways Arrive and Gloucester Still Booms - for now

It was during the 1840s that the railways arrived at Gloucester with lines brought into the docks (much later at Sharpness docks in 1875, and Bristol docks in 1877) by the two locally operating railway companies. The Midland Railway, from their station in Gloucester on the Bristol and Gloucester Railway, serviced the eastern side of the docks, and the Great Western Railway, via its branch line from south wales that ran along the western bank of the Severn, serviced the western side of Gloucester docks. These lines once established were increasingly used to distribute imports from the docks directly to Birmingham and the Midlands, and therefore in competition, at first with the upstream river and canal routes out of Gloucester, but as we will see, later with the Ship Canal itself.

The railways, the significant investment in the new docks and quays, lower import tariffs and with the Midlands being at the centre of the industrial revolution, all contributed to a dramatic boom in foreign imports, especially during the 1850s and 60s. According to Hugh Conway-Jones and his amazing 'Gloucester Docks' website, "corn came from northern Europe and the Black Sea ports situated around the mouth of the Danube, further warehouses were constructed and three flour mills were established. Timber came from the Baltic, North America and the arctic coast of Russia, and new timber yards and saw mills were established beside the canal south of Gloucester. Other imports included wines and spirits, oranges and lemons, and bones and guano for fertiliser. Unfortunately, salt was still the only regular export, and most vessels chose to go elsewhere to find a return cargo".

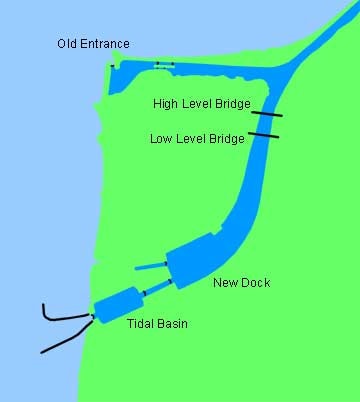

Sea-Going Ships Increase in-size Prompting an Upgrade at Sharpness

During the course of the 19th century, the size of vessels in service tended to increase, with schooners and barques being the most common types of sailing vessels, and there was a growing use of steamers. With the increasing size of ships, particularly steamers, the canal entrance at Sharpness was deemed to be inadequate and many of the large ships that could enter the canal couldn't do so fully laden. The original canal entrance at Sharpness comprised of one pair of entrance gates, a tidal basin and two locks. It had no provision for cargo handling, and all ships continued up the canal to discharge at Gloucester. Because of the high tidal range of the Severn (one of the highest in the world), vessels could only enter and leave the basin during a short period around the time of high water. When the water in the river reached the level in the tidal basin the entrance gates were opened, departing vessels went out, and arriving vessels entered, and the gates were closed. Vessels could then take their turn to lock up to the canal level and continue on their way to Gloucester.

The Canal Company therefore built a new entrance, with locks gates double the size of those on the original entrance, and a dock at Sharpness which, when opened in 1874, could take the largest ships of the day once again and allowed the growth in imports to continue. The smaller vessels came up the canal as before, whilst cargoes from the larger ships were transhipped at Sharpness and brought up the canal in barges and lighters. In 1875 the railways arrived at Sharpness Docks courtesy of the Midland Railway which connected the port via a branch line to their Bristol and Gloucester Railway main line. Gloucester Docks still continued to thrive due to the ongoing rise in trade associated with a booming British export economy, with regular services to continental ports.

Bristol Radically ups its' Port Game

Competition with Bristol entered a new phase in 1877, when entrepreneurs opened, what is now known as, the Avonmouth Old Dock, on the north bank of the River Avon just as it enters the Severn Estuary. The goal was to take traffic away from the heavily congested Port of Bristol, located some 7 miles inland in the city centre, and which also offered the advantage of avoiding the need for ships to enter and navigate the highly tidal and meandering River Avon that prevented boats over 300 feet (91m) in length from reaching the harbour. Initially it struggled for business, but in 1884 the Bristol Corporation, which owned the Port of Bristol, acquired the dock at Avonmouth, as well as the nearby Portishead Docks located directly on the Severn Estuary, a little to the south of the mouth of the river Avon. Having the same organisation running the City and the Avonmouth Docks was a recipe for success and Avonmouth prospered. In 1908, as part of ongoing competition, mainly with the port in Liverpool, an additional port was also built at Avonmouth, the Royal Edward Port, but with direct access to and from the Severn estuary and the Bristol Channel beyond. The Royal Edward Port was linked to Avonmouth Old Dock, thereby also providing the older dock with direct access into the Severn Estuary as well.

Sharpness Docks Rise and Gloucester Docks Decline but the Ship canal Still Booms

Ongoing technological progress in the form of railways and large steam ships had started to change the trade dynamic, especially for Gloucester. By the early years of the twentieth century, the increase in the size of merchant ships, particularly steamers, meant that a growing proportion of the goods coming to Gloucester arrived in barges and lighters from Sharpness or other Bristol Channel ports. Much of the corn, after being transhipped at Sharpness, was sent straight up the Ship Canal and on to the Midlands without any need to unload at Gloucester docks, and this in turn led to a decline in the use of the warehouses at Gloucester. In 1905 traffic on the Ship Canal exceeded one million tons for the first time, but while the Ship Canal was very busy, emphasis on trade had shifted from Gloucester to Sharpness.

Railways Change the Dynamic, Disrupting Trade Routes, Giving Merchants and Industrialists Multiple New Logistical Options

The railways gave merchants and industrialists many extra options for the transport of goods and this increased competition and reduced fees and costs. Trains could not only carry more than the canals but could transport people and goods far more quickly than the walking pace of the canal boats. Not only were the Midland Railway and the Great Western Railway servicing both Sharpness and Gloucester ports, they had also been servicing the old docks in the centre of Bristol since 1872 and the docks at Avonmouth since 1877, as well as of course, all the major towns and cities of Britain via the national railway network. Most of the investment that had previously gone into canal building was diverted into railway building. An exception to this stagnation was the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal in the 1890s using the existing River Irwell and River Mersey, to take ocean-going ships into the centre of Manchester via its neighbour Salford.

Canals Decline

The railways meant that goods could be transported by train from Sharpness to Gloucester, and more significantly to Birmingham and the Midlands, and therefore potentially completely by-passing the whole canal and river system between Sharpness, Gloucester, Worcester and Birmingham. Furthermore with larger more modern port facilities now available at Bristol, there was the option for goods to be brought into Bristol instead of Sharpness and distributed by railway to the Midlands, by-passing the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal and its ports completely. Not only that, the majority of UK's railway network was established by the 1870s, which meant that Birmingham was easily accessed by rail from the much larger port at Liverpool meaning that even Bristol could be by-passed if desired.

During the second half of the 19th century, many canals were in decline and the amount of cargo carried on the canals had fallen by nearly two-thirds, lost mostly to railway competition. Canal companies lowered charges to try to remain competitive. The less successful canals (particularly narrow-locked canals, whose boats could only carry about thirty tons) failed quickly while wider canals such as the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal remained viable. The smaller canals that survived through the 19th century were those that occupied niches in the transport market that the railways had missed, or by supplying local markets such as the coal-hungry factories and mills of the big cities. During the 19th century, in much of continental Europe, the canal systems of many countries such as France, Germany and the Netherlands, were modernised and widened to take much larger boats. This however never occurred on a large scale in the UK, mainly because of the power of the railway companies who owned most of the canals and saw no reason to invest in a competing form of transport.

Railways and Shipping Contract

The 20th century brought competition for both canals and railways from road haulage. During the 1950s and 1960s freight transport on the canals declined rapidly in the face of mass road transport. Coal was still being delivered to waterside factories that had no other convenient access. But many factories that had formerly used coal either switched to using other fuels, often because of the Clean Air Act of 1956, or closed completely.

The decline in the national canal industry was followed by a major decline in the railways. The railways peaked around the First World War and the length of national track levelled out at around 20,000 miles. 1920 appears to have been the peak year for number of rail journeys (2.2 million); and rail freight by tonnage peaked in 1924. The growth in road transport during the 1920s and 1930s greatly reduced revenue for the rail companies, who accused the government of favouring road haulage through the subsidised construction of roads.

After 1945, for both practical and ideological reasons, the government decided to bring the rail service into the public sector. According to Loft (2006), it was in this context that the Beeching report, The Reshaping of British Railways, was published in 1963. Intended to restore commercial viability under a new Railways Board, the report recommended closing uneconomic lines and stations, developing inter-city routes and overhauling freight with a combined road-rail container service. The effects of Beeching were drastic. Some 7,000 route-miles of the total 18,000 route-miles were cut by 1970, the number of stations was reduced by almost two-thirds and the rail workforce almost halved.

Decline of Britain as a Major Maritime Nation, Shift Towards Containerisation

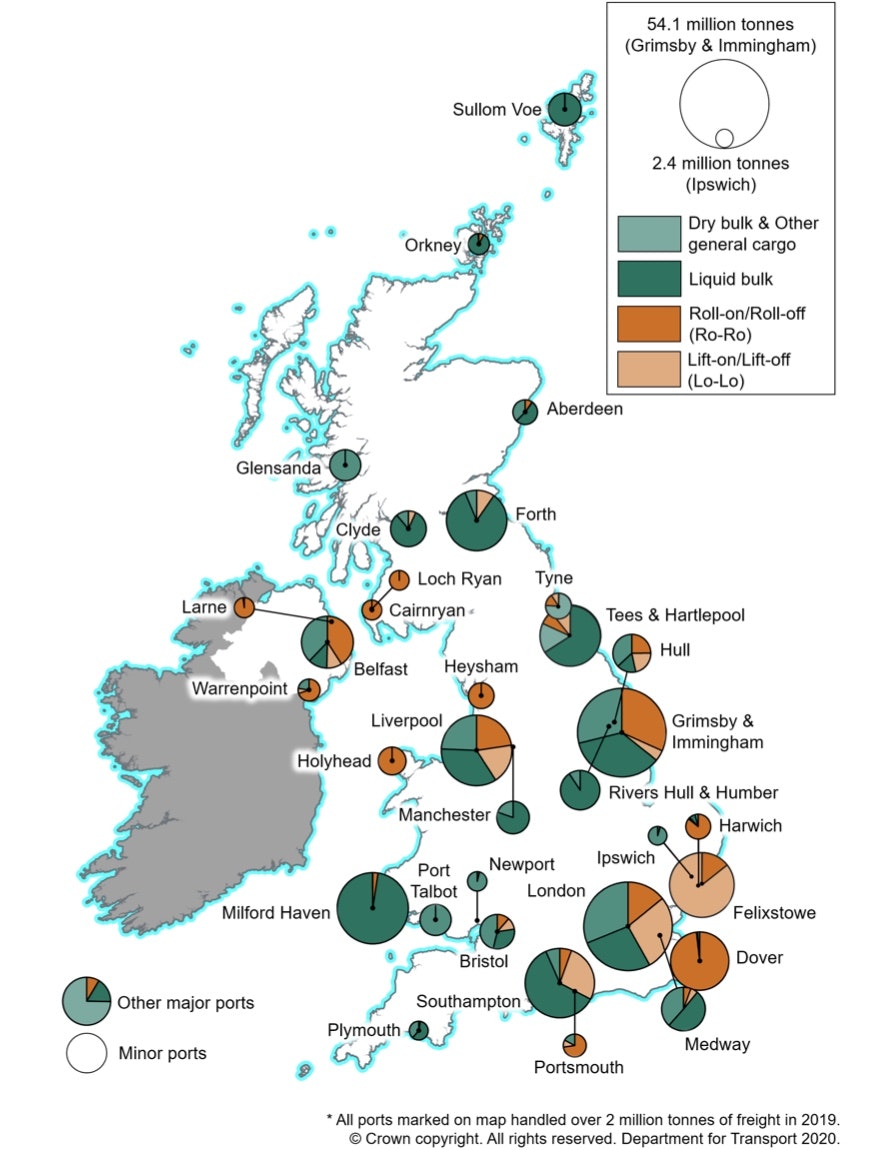

Britain entered the twentieth century as the world’s leading maritime power but its share of world tonnage fell from 43% in 1914, to 26% in 1938. The falling share of the world shipping trade in freight continued after the second world war. The demise of commercial trade along the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal was due to the demise of the manufacturing industry in Birmingham and the UK as a whole, as well as the managed closure of most of the nation's heavy industry, including coal mining. By 1970 the UK’s share of world tonnage had shrunk to a mere 11%. With the uptake of containerisation the historic pattern of Britain’s ports changed: Felixstowe and Southampton emerged as the most important sites for the new containers, Immingham for bulk goods like coal, eclipsed the old ports of London and Liverpool. This shift however enabled a renewed growth in cargo after 1990. The orientation away from the Atlantic trade to Europe was confirmed by the expansion of Folkestone and Dover for cross-Channel traffic from the later 1950s.

Gloucester Docks Cease Trading as a Commercial Port, Bristol and Liverpool Ports get an Upgrade and Sharpness Hangs on.

The Gloucester and Sharpness Canal Company was nationalised in 1947, and the new management set about encouraging more sea-going ships to come up to Gloucester. The docks also remained busy with barge traffic well into the 1960s. By the mid-1980s commercial traffic on the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal had largely come to a halt with the canal and the docks at Gloucester being given over to pleasure cruisers. Today the Sharpness is a minor port in terms of tonnage handled attracting trade largely from northern Europe that includes cement and fertiliser, grain and coal. It is believed to be the most inland port in the country.

In 1972 the Port of Bristol Authority opened a new large deep water Royal Portbury Dock on the southern bank of the river avon opposite the Royal Edward Dock, also with direct access to the Bristol Channel. It rendered the old Bristol City Docks in the Floating Harbour redundant as a commercial dock. In 1991 the two Avonmouth docks as well as the new Royal Portbury Dock were was privatised, under 'The Port of Bristol Company', and is today one of the UK's top15 ports. Bristol is still a major port, ranked around 15th in terms of tonnes of freight, which includes the handling of over 750,000 new cars per year for example, however just like Gloucester the old floating harbour in the city centre is now just for pleasure, although both are huge assets in terms to their intrinsic value. The docks in Liverpool moved further north up the Mersey estuary and into Liverpool Bay as previous docks grew too small and they were too susceptible to silting up. Liverpool docks stretch for over 7.5 miles (12.1 km), the largest enclosed interconnected dock system in the world.

According to Andrews (2018), the orientation of trade and business towards the European Union after Britain joined in 1973 reinforced the economy of London and the south-east. In shipping, ports facing out to the Continent – Felixstowe, Harwich, Folkestone, Dover, Southampton – thrived, while ports oriented to the Atlantic trade, like Bristol, Liverpool and Glasgow, suffered. From the 1930s, the gradual decline of the docks and shipbuilding in Liverpool and Glasgow went hand in hand with larger economic and demographic decline, culminating in an urban ‘crisis’ in the 1970s and1980s.

So Who Won the Trade War?

In terms of port trade Liverpool was the clear winner of this trade war, with Bristol doing well to remain significant to this day. Liverpool during much of the 19th Century the busiest and wealthiest port in the world. Today, however it's not even the busiest in the UK. Grimsby and Immingham on the North Sea coast of England, followed by London are the UK's top two ports, which ranked as the 71st, and 95th busiest ports in the world respectively in 2015 with third placed Milford Haven in South Wales along with Liverpool not even making the top 100. Felixstowe was however was ranked in 2015 as the 36th busiest container port in the world by tonnage handled.

Despite the UK handling 43% of world trade at the turn of the 20th century, today the UK's biggest port handles less than 10% of what Shanghai, the world's biggest port, handles. Here in lies the reality, while the trade wars between Bristol, Gloucester and Liverpool for supremacy of the UK's west coast sea trade were mammoth by 19th century standards they have been superseded by much bigger trade routes as a result of the shifting trade powers of the world's nations, most notably away from being dominated by the UK, Europe and the USA towards a broader range of nations dominated by China.

Never-the-less, the 19th Century brought great wealth to Britain, especially those cities such as Birmingham and Liverpool that were well positioned to capitalise on the industrial revolution due to their manufacturing and maritime strengths respectively. Gloucester's rise and fall was dramatic given that it went from having no sea port to having a thriving one and back again. Liverpool, while still an important port city, has seen its fortunes rise and fall dramatically too - going from a population of less than two thousand in 1600, to almost a 850,000 in the 1930's only to have fallen by approximately 50% since then. Birmingham's population has remained more-or-less the same since the 1930's, and is still an important manufacturing centre, in national rather than international terms, while Bristol's population peaked in the 1970's before falling marginally. In terms of population, in 2017, Birmingham is the second biggest city in the UK after London with 1.2 million people, Liverpool is 4th with 0.6 million people, Bristol is the 5th with 0.5 million people, and Gloucester is the 49th, with 147 K people. Sharpness is not even ranked as it has a population of less than 100 people.

In terms of Gross Value Added (GVA), a measure of the value of goods and services produced in an area, such as a city, per head of population, Birmingham in 2015 was ranked 3rd in the UK, Bristol 8th and Liverpool 11th. In terms of prosperity, the Legatum Institute, an international think tank and educational charity focused on promoting prosperity, in 2016 ranked the UK's 389 Local Authorities across multiple socio-economic factors using their Prosperity Index. Of our cities in this little study of the Ship Canal, Liverpool was ranked at 381, Birmingham at 377, Gloucester at 291, Bristol at 129, and Sharpness, which comes under the Stroud Local Authority, at 60. While these rankings are quite subjective it does give an indication that despite its wealth and prominence in the 19th Century, the people of Liverpool haven't prospered in terms of overall quality of life when compared too the rest of the country. Based on these rankings the people of Bristol seem to have prospered the most.

It seems incredible that such feats of engineering, as the Gloucester and Sharpness Ship Canal, and the docks at Gloucester, and even the floating harbour in Bristol and the older docks in Liverpool, are now little more than recreation sites. They did however help make many merchants and industrialists very rich for over one hundred years, and played their roles in the industrial revolution and the pre-eminence of the Britain especially during the 19th century. The trade of the 19th century has given us some of the UK's most important cities today, such as Birmingham, Liverpool, Manchester and others such as Glasgow that haven't even been mentioned in this article till now. They may no longer have such global importance but they are critical to Britain today and help make this country what it is.

Today we are left with these historical gems to enjoy and marvel at, even though its really hard to imagine just how much endeavour, business and production was going on during the peak of their operation, compared to today where infrastructure development, and industrial and economic progress is much slower, and the economy and life as whole is much less dynamic. This period surely can only be compared to that of the industrialisation of modern-day China.

References

https://assets.publishing.serv...

https://canalrivertrust.org.uk...

https://tewkesburyhistory.org/...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/...

https://www.gloucesterdocks.me...

https://www.gloucesterdocks.me...

https://www.gloucesterdocks.me...

https://www.gloucesterdocks.me...

https://www.canalboat.co.uk/wa...

https://www.thegeographist.com...

https://lif.blob.core.windows....

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/...